by Mark J. Manhart DDS, 1982

INTRODUCTION

Calcium compounds have shown to be valuable materials in dentistry for a hundred years [1]. Formulations of calcium with esters exhibit remarkable properties in the healing process of dental structures, namely, in periapical (root tip) and endodontic (root canal) tissues [2] [3] [4], in vital root resection procedures [5], and on pulp tissues [6].

Over a period of 16 years calcium compounds have been used by the present observer in the development of therapies for endodontic and periodontal (gum and bone) infections [3] [7]. Since periodontal disease is the most common degenerative disease in industrialized societies, the Calcium Method of Periodontal Therapy (CMPT) is of significant interest. Furthermore, the versatility of calcium-ester compounds extends into such diverse areas as dental implantology [8] and calcium deficiencies [9].

Therefore, this study was directed toward relationships among calcium compounds, periodontal disease, and calcium levels of saliva and blood. It is this observer’s hypothesis that CMPT is not only a sound and effective therapy, but could be related to the blood serum calcium level and calcium deficiencies. Research has indicated that one of the most responsive stores of calcium in the body to restore calcium imbalance is the alveolar bone, the delicate bone around the neck of each tooth as one of the tooth-supporting tissues, the periodontium (10). That is, the exact tissues directly and immediately affected by advanced periodontal disease and by the CMPT.

More recent stress studies by McCarron (11) relate low blood serum concentrates of ionized calcium to hypertension. Therefore, as part of the present hypothesis, a correlation could be drawn from any periodontal therapy that would provide excess free calcium ions to the periodontium and the blood serum calcium concentration. The present study may link elevated calcium levels during periodontal therapy to the calcium levels of the saliva and the periodontal tissues. In addition, the calcium treatments are very direct and long-term. Thus, a significant elevation in the salivary calcium levels or blood serum may reveal a calcium treatment for both periodontal disease and calcium deficiency diseases.

METHOD

Regardless of the severity of the subject’s periodontal condition, all were treated in a consistent manner in order to determine the responsiveness of salivary calcium levels or the blood serum to the calcium material. The study population consisted of volunteers from the observer’s dental practice who were entered consecutively into the protocol having responded positively to an invitation to participate in a study of periodontal disease. The data collection was taken in the private office as part of a special approved project and informed consent was obtained from each subject. General information was given to the subjects prior to the initial appointment of the study. After records and a medical history were taken to screen out persons with other degenerative diseases or drug dependencies, the protocol was explained. Upon acceptance of the informed consent agreement, the observer made a visual exam and periodontal probe survey of the mouth and periodontium.

The subjects were then categorized in Groups and the tests taken in Sequence as in Figure 1 BELOW.

SUBJECTS

Groups:

- Having active presence of periodontal disease.

- Having a history of periodontal disease, but no active presence.

- No history of periodontal disease, and none at the time.

The series of tests for each recording were taken in the following sequence:

Sequence:

- Sublingual temperature

- Saliva sample

- Blood pressure

- Venous blood sample

The sublingual temperature was recorded over a seven to ten minute period. The observer measured the systolic and diastolic blood pressures with the subjects in a recumbent position at least two times consecutively for each recording. The mean blood pressure in mm Hg was then calculated and recorded. Saliva samples were obtained with 0.05 ml pipettes.

NOTE: Gingival blood samples were not designed into the protocol due to the difficulty in obtaining adequate samples without incising the gingival tissue, and the risk of saliva contamination of the sample was too great. This was especially the case in subjects of Groups II and III. Also, the rapid response of the gingival tissue to the calcium treatment precluded easy access to gingival hemorrhage.

Venous blood samples were taken from the subjects’ fingertips without aid of a tourniquet. The four tests were ordered in the above sequence to minimize the effects that venous blood sampling might have on the blood pressure. The recording periods were:

- Immediately prior (before treatment)

- Ten minutes (post-treatment)

- Two days (post-treatment)

- Seven days (post-treatment)

A single dose of a calcium-ester paste compound (0.4 cc) was administered into the interdental spaces and periodontal pockets of the periodontium surrounding all maxillary and mandibular dentition (teeth). All of the subjects had most or all of their anterior and posterior teeth. Injection of the entire dosage was accomplished without anesthesia, without pain, and within two minutes.

The subjects’ dietary habits were monitored by recording their general food intake for the two days following treatment. Instructions were given that the calcium material is antimicrobial and to rinse the mouth only occasionally during this two-day period, and not to brush the teeth until after the tests were recorded on the second day. Blood samples were taken from their fingertips and centrifuged within two hours to separate out the serum. Those samples were then frozen along with the saliva samples until all the test samples were gathered from all the subjects.

A determination of the present study was the amount of calcium in the serum just before treatment, ten minutes after treatment, two days after treatment, and seven days after the single periodontal treatment with the calcium-ester compound. The method of determination was Atomic Absorption (AA) Spectrometry. The principle is the concentration of calcium in solution is directly proportional to the light absorbed at a wavelength characteristic of calcium atoms. The absorption values obtained were then interpreted off an absorption curve generated by 0, 1, 4 ppm calcium. The standard attempts to match the matrix of serum by containing sodium and potassium in levels similar to those normally found in serum.

RESULTS

The distribution of subjects by age, sex, dietary calcium intake and periodontal condition were recorded as Characteristics of Subjects. The population included 14 subjects ranging in age from 19 to 68 years, average 33 years, six male and eight female. Five subjects presented with active periodontal disease (Group I ), five had a history and no active presence (Group II ), and four had no history of nor any periodontal disease (Group III ). At the two-day interval after treatment, it was recorded that the dietary intake of the subjects consisted of None-to-Four Servings, averaging 1.8 Servings of calcium-rich foods such as milk, cheese, or green vegetables.

The sublingual temperature, dietary calcium intake, and the periodontal conditions were observed during the treatment period. The only significant changes occurred on subjects in Group I (active perio. dis.) and Group II (history of perio. dis., no presence) where there was visual evidence of less gingival inflammation, less bleeding upon probing, and an abatement of sensitivity. The mean sublingual temperatures of the population, the mean blood pressures, the mean saliva and serum calcium levels, parts per million (ppm), over the entire treatment period were calculated and recorded. There were no significant changes in temperatures before or throughout the treatment period.

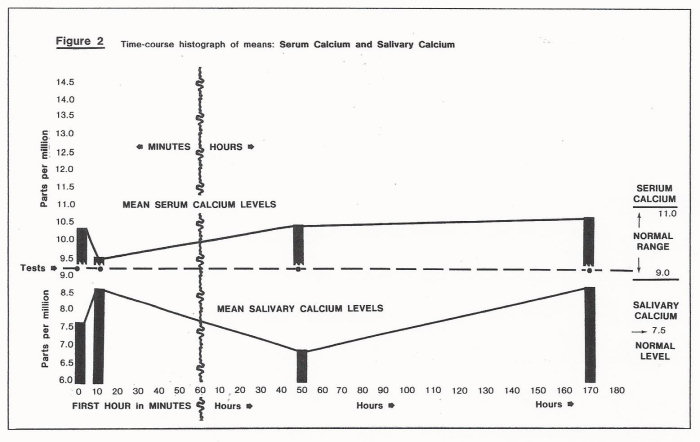

The mean blood pressures of the population were slightly lower at the ten-minute post-treatment test, slightly lower at the two-day interval, and then returned to the original levels by the seven-day test as in Figure 2 BELOW.

However, the mean saliva calcium level for the population rose dramatically by the ten-minute post-treatment test, dropped slightly below their original level by the two-day test, and returned to an even higher level than the point of the ten-minute test. With regard to the mean serum calcium level, an opposite response was observed. The blood serum calcium level dropped by the ten-minute test, and returned to the initial pre-treatment level by the second day, and then continued to rise toward the seventh day to a higher level, above the pre-treatment level.

When the subjects were analyzed within their own Groups, the results were as expected: Group I (active perio.dis.) averaged 37 years of age, Group II (history of perio. dis. no presence) averaged 44.8 years old, and Group III (no history of perio. dis.) averaged 26.7 years of age.

It was also observed that Group II (history of perio.dis. no presence) averaged a serum calcium level of 12.26 ppm before treatment, i.e. above average. After treatment their serum calcium levels consistently rose to 13.26 ppm, whereas Groups I and III levels varied up and down randomly. Before treatments the mid-age Group I (active presence perio. dis.) showed a lower level of salivary calcium. This level increased in all cases at the ten-minute post-treatment test and continued higher to the seventh day.

The older Group II (history of perio. dis. no presence) had more calcium in their serum before treatment, however, their levels dropped upon treatment by the ten-minute test and returned to their original high by the second day test and increased by the seventh day. The salivary calcium levels of this Group II, however, decreased between the treatment time and the two day level, and then tended to stay down. That is, 80% were down just after the ten-treatment and 60% at the seven days post-treatment. This data seemed to raise a question of why the salivary calcium level would be reduced even though a high concentrate of calcium material was in the mouth at this time. The answer may be part of subsequent analysis of the subjects in terms of their sex. Group II also showed higher serum calcium levels before treatment and the calcium materials apparently added to that level for at least two days, especially in the older subjects, Group II. This group had no other significant patterns develop despite a history of periodontal disease and no presence evident.

When the data was also analyzed in terms of sex of the subject, an interesting pattern emerged. At the outset the serum calcium levels of 83% of the males were normal, while the female levels were equally scattered throughout the range. Over the seven-day period, looking at the increases and reductions in serum calcium levels, and setting aside the few average readings, it became evident that males were doing one thing and the females another. The serum calcium levels of 70% of the males were down, while 76% of the female levels were up.

DISCUSSION

Periododntal disease has been correlated with blood pressure conditions, namely, hypertension, which coincides with a loss of vital calcium from the periodontal (alveolar) bone of the mouth to the vascular system [10]. Blood calcium levels are known to be controlled closely by the endocrine system, and recent studies have related blood pressure to the blood calcium level [11].

The results of the present investigation demonstrate the reliability of the CMPT, and present interesting corollaries to calcium levels of the serum. In terms of diet, it should be noted that an individual’s calcium level can reflect a life style, eating habits, or explain the variance of individual results. The normal calcium level of the serum is 9-11 ppm. Although this study reports the mean value in this range, it can be noted that the serum calcium levels did rise by 0.2189 ppm seven days after treatment. This data were analyzed with a least-squares computer program to fit the straight line with the standards and the calcium values interpreted from the line and the instrument’s reading from each sample.

The value of calcium in saliva is 7.50 ppm, and it can be further noted that by the seventh day post-treatment these levels did rise by 1.2693 ppm. The study indicates that there is less available calcium in the saliva at the time of periodontal disease activity, and the CMPT initiates a rapid and sustained increase in the salivary calcium during treatment.

Another interesting aspect of the study was that while the salivary calcium levels were rising significantly at the outset of the therapy (ten minutes post-treatment readings), the serum calcium levels were dropping by 0.84 ppm. Nonetheless, the calcium concentrations in the serum did continue to rise above their initial levels by the second day and thereafter. This would indicate that there is less calcium the in the serum at the time of periodontal disease activity. It should be noted that much of the treatment material administered to deep subgingival spaces remained for an extended period of time, i.e. several days despite normal brushing procedures.

It is apparent that local site administration of the calcium compound into the periodontal tissues elicits a rapid and extended serum calcium response and alteration. The CMPT apparently replenishes the low level of calcium in the midst of periodontal infection. In addition, the divergent response of serum calcium level to the treatment may be also associated with the sex and the age of the subject. One might speculate as to what happens to the stochiometric level (quantity of chemical reaction) of the calcium material in the initial period of the periodontal treatment. The answer may bear upon the subject’s capacity for utilizing free calcium. This may also explain why the calcium level of Group I (active perio. dis.) was lower and the serum calcium level of Group II (history of perio. dis. no presence) was higher.

Inasmuch as both normal and infected periodontal tissues respond favorably to this treatment, it may be suggestive of a long-term resource of dietary calcium as well as a mode of controlling and healing periodontal disease. This calcium-concentrated therapy would seem valuable in the context that calcium deficiency disorders are common symptoms for many patients with hypertensive, osteoporotic, and periodontal disease conditions.

SUMMARY

Local administration of the CMPT, whether the periodontium is infectious or healthy, does not seem to interfere with the regenerative capacity of the periodontal or vascular tissues. Furthermore, this periodontal treatment has no deleterious effects on sublingual temperature, blood pressure, nor salivary and serum calcium levels. On the contrary, the calcium material affects an improved periodontal condition. Although the therapeutic dose altered the salivary and serum calcium initially, normal levels were re-established rapidly. The study did reveal significant fluctuation and subsequent rise in salivary and serum calcium levels, and a possible correlation with sex and age. Finally, a direct correlation of this periodontal therapy to treatment of other calcium deficiencies cannot be made at this time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr. William deGraw

Ms. Fredricka Laux

Dr. Thomas Steg

Copyright 1982

BIBLIOGRAPHY available upon request